| Should the modern citizen-consumer be doing more to support liberal democracies? Rod Nixon Originally published (in shorter form) by the Asia & The Pacific Society (APPS) Policy Forum on 17 September 2019. | Free Trade and Authoritarian States In retrospect, the accession of China to the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 2001 was based on extraordinary optimism that a large, populous, economically powerfully authoritarian state would pose no threat to the interests and aspirations of liberal democracies. The belief in a link between capitalist economic success and political liberalisation has been pervasive. However, the truism that democracy is good for business, with the implication that the reverse also holds, is now ailing. |

In the present day, an uneasy relationship exists between the consumers of liberal democracies, and the authoritarian states whose workers produce much of the merchandise these ‘democratic citizens’ consume. In the case of the growing industrial giant of China, the lack of certainty about a link between capitalist economic success and liberalisation was reinforced at the 2018 annual sitting of the Chinese National People’s Congress, when Premier Xi Jinping was appointed President-for-life.[1] The following year, in the highly successful automobile-producing nation of Thailand,[2] the ruling military passed up yet another opportunity to hold a genuinely free and fair election.[3]

Linking the 2019 Freedom House ‘Freedom in the World’ assessment (Freedom House 2019), to the 2019 World Bank Ease of Doing Business assessment rankings (World Bank 2019:5), it can be seen that of the top 50 countries (of 190 ranked), only 31 are ‘Free’ according to the Freedom House criteria. A further 10 are classified as ‘Partly Free’ (including Singapore, Hong Kong and Malaysia), with the remaining nine classified as ‘Not Free’. Notably, the latter group includes China, the Russian Federation and Thailand, which combined have a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of US$15.5 trillion based on 2017 World Trade Organisation (WTO) figures (WTO 2018). Notably, the authoritarian state of China was the world’s leading exporter of merchandise in 2017, with merchandise exports valued at US$2.26 trillion.[4] What a perverse outcome therefore, that free trade - in the hope of promoting liberalisation – is fostering the development of an authoritarian superpower.

The high-profile exceptions to the supposed rule that economic success necessarily correlates to respect for democratic rights and human freedom highlight two things. The first is the need for a more critical approach to the study of democratic transition. The second is the potential need for new drivers of change.

Merchandise Imports from Authoritarian States into ‘Prosperous Liberal Democracies’

In the interests of exploring potential drivers of change I have taken a look at recent (2016-2017) WTO data. I have framed my analysis around the question of trade between Prosperous Liberal Democracies (PLDs) and authoritarian states. For the purposes of the analysis I define PLDs as members of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) that are also accorded ‘Free’ status in the 2019 Freedom House index. While observance of democratic principles is a key requirement for membership of the OECD,[5] the augmented definition used in this article addresses the fact that a number of OECD countries have slipped in their implementation of democratic principles since becoming members. Cross-referencing the 36 OECD countries[6] with the 2019 Freedom House index (Freedom House 2019), it can be seen that only 33 of the 36 OECD countries currently hold ‘Free’ status with Freedom House. Of the remaining three, two (Hungary and Mexico) are rated only ‘Partly Free’ while the remaining country (Turkey) is rated ‘Not Free’.

WTO data on merchandise imports by the world’s 33 PLDs, [7] as defined above, clarifies the extent to which PLDs source merchandise from authoritarian states.[8] Notably:

What is the Potential for Exerting Leverage?

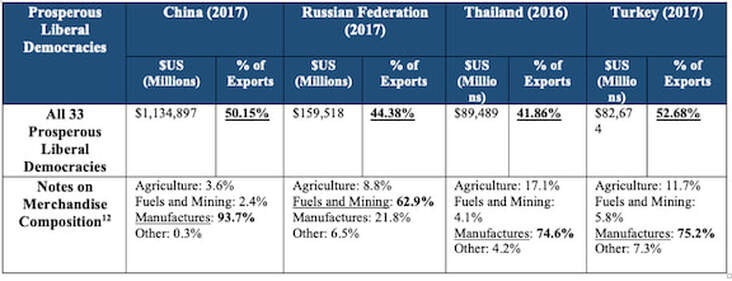

To gauge the potential for leverage it is also important to examine merchandise trade between authoritarian states and PLDs from the opposite angle. Based on World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS) data (World Bank 2017) from the 2016-2017 period, the extent to which key authoritarian states benefit from merchandise exports to PLDs can be assessed. The following table presents summary data on this area for the authoritarian states of China, Russian Federation, Thailand and Turkey.

Table 1: Total Share of Merchandise Exports from Authoritarian States Imported into Prosperous Liberal Democracies[11]

Linking the 2019 Freedom House ‘Freedom in the World’ assessment (Freedom House 2019), to the 2019 World Bank Ease of Doing Business assessment rankings (World Bank 2019:5), it can be seen that of the top 50 countries (of 190 ranked), only 31 are ‘Free’ according to the Freedom House criteria. A further 10 are classified as ‘Partly Free’ (including Singapore, Hong Kong and Malaysia), with the remaining nine classified as ‘Not Free’. Notably, the latter group includes China, the Russian Federation and Thailand, which combined have a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of US$15.5 trillion based on 2017 World Trade Organisation (WTO) figures (WTO 2018). Notably, the authoritarian state of China was the world’s leading exporter of merchandise in 2017, with merchandise exports valued at US$2.26 trillion.[4] What a perverse outcome therefore, that free trade - in the hope of promoting liberalisation – is fostering the development of an authoritarian superpower.

The high-profile exceptions to the supposed rule that economic success necessarily correlates to respect for democratic rights and human freedom highlight two things. The first is the need for a more critical approach to the study of democratic transition. The second is the potential need for new drivers of change.

Merchandise Imports from Authoritarian States into ‘Prosperous Liberal Democracies’

In the interests of exploring potential drivers of change I have taken a look at recent (2016-2017) WTO data. I have framed my analysis around the question of trade between Prosperous Liberal Democracies (PLDs) and authoritarian states. For the purposes of the analysis I define PLDs as members of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) that are also accorded ‘Free’ status in the 2019 Freedom House index. While observance of democratic principles is a key requirement for membership of the OECD,[5] the augmented definition used in this article addresses the fact that a number of OECD countries have slipped in their implementation of democratic principles since becoming members. Cross-referencing the 36 OECD countries[6] with the 2019 Freedom House index (Freedom House 2019), it can be seen that only 33 of the 36 OECD countries currently hold ‘Free’ status with Freedom House. Of the remaining three, two (Hungary and Mexico) are rated only ‘Partly Free’ while the remaining country (Turkey) is rated ‘Not Free’.

WTO data on merchandise imports by the world’s 33 PLDs, [7] as defined above, clarifies the extent to which PLDs source merchandise from authoritarian states.[8] Notably:

- Authoritarian states are the leading source of merchandise imports for six of the 33 PLDs. (Specifically, Australia, Chile, Japan, New Zealand, South Korea and the United States. The source country is China in all cases.)

- Authoritarian states are among the top two sources of merchandise imports for 27 of the 33 PLDs. (The leading source country in these cases is China followed by the Russian Federation.)

- Authoritarian states are among the top three sources of merchandise imports for 32 of the 33 PLDs.

- The data indicates annual merchandise imports by PLDs from authoritarian states of US$1.555 trillion for 2016-2017. For comparative purposes, total exports of merchandise from China (the world’s leading merchandise exporter) for the same period was US$2.26 trillion (WTO 2018:80)

- Given the total population of the PLDs included in the analysis of 1.067 billion people (2015 figures),[9]this equates to a minimum average annual spending on merchandise sourced from authoritarian states of US$1,456.96 for every citizen of a PLD (not including local/domestic profits, costs and taxes). On average, a minimum of 13.47 per cent of merchandise imports into PLDs is sourced from authoritarian states.[10]

What is the Potential for Exerting Leverage?

To gauge the potential for leverage it is also important to examine merchandise trade between authoritarian states and PLDs from the opposite angle. Based on World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS) data (World Bank 2017) from the 2016-2017 period, the extent to which key authoritarian states benefit from merchandise exports to PLDs can be assessed. The following table presents summary data on this area for the authoritarian states of China, Russian Federation, Thailand and Turkey.

Table 1: Total Share of Merchandise Exports from Authoritarian States Imported into Prosperous Liberal Democracies[11]

As the data tabled above indicates, PLDs consume around 40 to 50 per cent of the merchandise exports of the featured authoritarian states. This data suggests that authoritarian states are significantly exposed to a boycott by PLD consumers, assuming the latter can be sensitised at scale to take action.

It should also be noted that the exposure of particular authoritarian states to possible consumer boycott action is likely to vary according to the profiles of their particular merchandise exports (which includes the main categories of manufactures, agricultural products, and fuels and mining products). Of the authoritarian states profiled above, manufactures represent the majority share of merchandise exports for China (93.7%), Thailand (74.5%) and Turkey (75.2%). Given that the origin of manufactures is generally labelled, a consumer boycott of manufactures sourced from authoritarian states could be relatively straightforward to implement (sensitising consumers perhaps representing the main challenge). Meanwhile, the majority of Russia’s merchandise exports fall into the category of fuels and mining (62.9%), with manufactures at only 21.8%. For Russia and other authoritarian states such as Saudi Arabia[13] for which the main category of merchandise export is fuels and mining (potentially unlabelled products), the organisation of effective consumer action would require a strategy that requires suppliers to clearly state the origin of such products as petroleum fuel. Added to this would be the challenge of promoting alternatives to fuels and mining products traditionally or commonly sourced in authoritarian states.

Of the authoritarian states profiled above, China would appear most exposed to an effective consumer boycott of authoritarian states. Not only is China the world’s largest single exporter of manufactures (at US$2.26 trillion),[14] but 93.7% of its merchandise exports are manufactures and over half its merchandise exports (50.15%) were being imported into prosperous liberal democracies at the time of the generation of the featured trade data.

Is it Time to Ditch Free Trade and Buy from Democracies?

Given what Freedom House (2019:4-5) describe as a 13-year decline, from 2005 onwards, in ‘political rights and civil liberties’ globally, the merchandise import patterns of the world’s PLDs deserve critical attention.

The scale at which ‘democratic’ consumers have been importing merchandise from authoritarian regimes raises the question of the extent to which the material quality of life of the modern democratic citizen has become dependent on the input of workers operating under authoritarian control.[15]

In terms of principles, what does a high level of merchandise importation from authoritarian states suggest about the commitment to human rights and democracy, of citizens of the world’s leading democracies? In the case of Australia, the nation’s enthusiasm for electoral participation is so strong that the population either supports or tolerates compulsory voting, yet the nation’s leading source of imported merchandise is the authoritarian state of China. Given the increasing uncertainty that capitalist economic success leads inevitably to democratisation, there would appear a pressing need for attention to the following issues and questions:

In recent decades, various campaigns have sought to influence consumer spending patterns in the interests of a range of specific environmental and social causes. Examples of these include the Rainforest Alliance Sustainable Agriculture Network (SAN)[16] and the Marine Stewardship Council.[17] Other campaigns have focussed on human rights issues in particular contexts, with recent examples including a celebrity-led boycott of Brunei after the nation moved to implement Sharia law,[18] and a Codepink boycott of Saudi Arabia for an array of reasons.[19] And yet, to date there has been no systematic attempt to influence consumer spending aimed at leveraging ongoing democratisation in authoritarian states. This is notwithstanding the critical importance of the liberal democracy as the political system that has provided the space for multiple other agendas to be advanced over the last century, across a range of areas spanning human rights, environmental sustainability, gender equality and more.

The Challenge for Citizen-Consumers

As the ultimate custodians and beneficiaries of democracy, it may be up to citizens, or citizen-consumers, to lead a change towards procurement practices that favour democracies. While tariff regimes like the one being currently implemented or threatened by United States President Donald Trump may have an impact, Trump’s behaviour is unpredictable. In any case, states may be bound by commitments to free trade, or addicted to trade partnerships with authoritarian states for economic reasons. No such factors prevent private individual, businesses and local governments from exercising moral judgement in their procurement choices. Furthermore, a boycott of authoritarian regimes that originates with citizen-consumers could contribute to the containment of authoritarian states without implicating the leaders of liberal democracies and thereby risking inter-state tension.

* * *

A change in consumer behaviour of magnitude sufficient to leverage democratic change in authoritarian states would represent no small achievement. A clear opposing force could be potentially higher prices associated with procuring from alternative sources where externalities such as environmental approvals and worker protection safeguards contribute to increased costs. Yet there are historical precedents for significant changes to economic patterns on the basis of human rights advances.[20] Furthermore, the rise of India as a democratic, if troubled, manufacturing power may introduce new dynamics. Emphasis on the virtue of procuring from democratic nations could encourage authoritarian manufacturing countries to compete with more democratic rivals.

There is unquestionably much about governance in liberal democracies that could be improved. Citizen involvement is often limited to periodic participation in polls, governing parties may deviate from stated positions and attempt to hide unethical conduct from public scrutiny on the pretext of ‘security’, populists may succeed in gaining entry to parliament or even control of government, and electorates themselves may prioritise short-term interests over long-term needs. Yet the world over, people have benefited from progressive political, human rights, and environmental changes that owe their origins to the freedom of inquiry and expression that flourishes in liberal democracies. Is it time for citizen-consumers to target their spending practices to help stem the global recession of liberal democratic values? Is it time to Buy Democratic?

It should also be noted that the exposure of particular authoritarian states to possible consumer boycott action is likely to vary according to the profiles of their particular merchandise exports (which includes the main categories of manufactures, agricultural products, and fuels and mining products). Of the authoritarian states profiled above, manufactures represent the majority share of merchandise exports for China (93.7%), Thailand (74.5%) and Turkey (75.2%). Given that the origin of manufactures is generally labelled, a consumer boycott of manufactures sourced from authoritarian states could be relatively straightforward to implement (sensitising consumers perhaps representing the main challenge). Meanwhile, the majority of Russia’s merchandise exports fall into the category of fuels and mining (62.9%), with manufactures at only 21.8%. For Russia and other authoritarian states such as Saudi Arabia[13] for which the main category of merchandise export is fuels and mining (potentially unlabelled products), the organisation of effective consumer action would require a strategy that requires suppliers to clearly state the origin of such products as petroleum fuel. Added to this would be the challenge of promoting alternatives to fuels and mining products traditionally or commonly sourced in authoritarian states.

Of the authoritarian states profiled above, China would appear most exposed to an effective consumer boycott of authoritarian states. Not only is China the world’s largest single exporter of manufactures (at US$2.26 trillion),[14] but 93.7% of its merchandise exports are manufactures and over half its merchandise exports (50.15%) were being imported into prosperous liberal democracies at the time of the generation of the featured trade data.

Is it Time to Ditch Free Trade and Buy from Democracies?

Given what Freedom House (2019:4-5) describe as a 13-year decline, from 2005 onwards, in ‘political rights and civil liberties’ globally, the merchandise import patterns of the world’s PLDs deserve critical attention.

The scale at which ‘democratic’ consumers have been importing merchandise from authoritarian regimes raises the question of the extent to which the material quality of life of the modern democratic citizen has become dependent on the input of workers operating under authoritarian control.[15]

In terms of principles, what does a high level of merchandise importation from authoritarian states suggest about the commitment to human rights and democracy, of citizens of the world’s leading democracies? In the case of Australia, the nation’s enthusiasm for electoral participation is so strong that the population either supports or tolerates compulsory voting, yet the nation’s leading source of imported merchandise is the authoritarian state of China. Given the increasing uncertainty that capitalist economic success leads inevitably to democratisation, there would appear a pressing need for attention to the following issues and questions:

- A proportion of every purchase of merchandise originating in an authoritarian state can be expected to be paid in tax to a non-democratic regime. All such resources are disbursed without the oversight of elected representatives, and a proportion may be used to suppress human freedoms (as in the case of ethnic and religious minorities in China) or potentially threaten the interests of liberal democracies. Accordingly, should citizens of liberal democracies be concerned about the impacts of purchasing significant volumes of merchandise from authoritarian states?

- What are the costs of no change to trade patterns between PLDs and authoritarian states. Can liberal democracies retain their prosperity and independence under such circumstances?

- Might the obligations of democratic citizens in the 21st century include purchasing merchandise sourced from democracies in preference to merchandise sourced from authoritarian states, in order to provide an incentive to national elites (and elements able to influence them, including transnationals) to prioritise and advance human rights and democratic values?

In recent decades, various campaigns have sought to influence consumer spending patterns in the interests of a range of specific environmental and social causes. Examples of these include the Rainforest Alliance Sustainable Agriculture Network (SAN)[16] and the Marine Stewardship Council.[17] Other campaigns have focussed on human rights issues in particular contexts, with recent examples including a celebrity-led boycott of Brunei after the nation moved to implement Sharia law,[18] and a Codepink boycott of Saudi Arabia for an array of reasons.[19] And yet, to date there has been no systematic attempt to influence consumer spending aimed at leveraging ongoing democratisation in authoritarian states. This is notwithstanding the critical importance of the liberal democracy as the political system that has provided the space for multiple other agendas to be advanced over the last century, across a range of areas spanning human rights, environmental sustainability, gender equality and more.

The Challenge for Citizen-Consumers

As the ultimate custodians and beneficiaries of democracy, it may be up to citizens, or citizen-consumers, to lead a change towards procurement practices that favour democracies. While tariff regimes like the one being currently implemented or threatened by United States President Donald Trump may have an impact, Trump’s behaviour is unpredictable. In any case, states may be bound by commitments to free trade, or addicted to trade partnerships with authoritarian states for economic reasons. No such factors prevent private individual, businesses and local governments from exercising moral judgement in their procurement choices. Furthermore, a boycott of authoritarian regimes that originates with citizen-consumers could contribute to the containment of authoritarian states without implicating the leaders of liberal democracies and thereby risking inter-state tension.

* * *

A change in consumer behaviour of magnitude sufficient to leverage democratic change in authoritarian states would represent no small achievement. A clear opposing force could be potentially higher prices associated with procuring from alternative sources where externalities such as environmental approvals and worker protection safeguards contribute to increased costs. Yet there are historical precedents for significant changes to economic patterns on the basis of human rights advances.[20] Furthermore, the rise of India as a democratic, if troubled, manufacturing power may introduce new dynamics. Emphasis on the virtue of procuring from democratic nations could encourage authoritarian manufacturing countries to compete with more democratic rivals.

There is unquestionably much about governance in liberal democracies that could be improved. Citizen involvement is often limited to periodic participation in polls, governing parties may deviate from stated positions and attempt to hide unethical conduct from public scrutiny on the pretext of ‘security’, populists may succeed in gaining entry to parliament or even control of government, and electorates themselves may prioritise short-term interests over long-term needs. Yet the world over, people have benefited from progressive political, human rights, and environmental changes that owe their origins to the freedom of inquiry and expression that flourishes in liberal democracies. Is it time for citizen-consumers to target their spending practices to help stem the global recession of liberal democratic values? Is it time to Buy Democratic?

Notes

[1] British Broadcasting Corporation (2018).

[2] According to an Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) report (ASEAN 2018), “Thailand is the 13th largest automotive parts exporter [shipping to over 100 nations] and the sixth largest commercial vehicle manufacturer in the world, and the largest in ASEAN”.

[3] An Asian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) interim report referred (AHRC 2019) to “fundamental democratic shortcomings” with the 24 March 2019 general election in Thailand.

[4] See WTO (2018:80). The United States was in second place with merchandise exports valued at US$1.55 trillion (WTO 2018:382).

[5] In its ‘Framework for the Consideration of Prospective members’, OECD restate (2017:4) the position that ‘OECD Members form a community of nations committed to the values of democracy based on rule of law and human rights, and adherence to open and transparent market-economy principles’.

[6] See OECD (2019).

[7] Based on review of merchandise import and other data included in ‘Trade Profiles 2018’ (WTO 2018) for the economies of Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxemburg, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, and United States.

[8] Note that imports into ‘prosperous liberal democracies’ from ‘Partly-free’ states are not included in the analysis.

[9] See UNDP 2017.

[10] The total is potentially significantly greater, as the WTO data (WTO 2018) used in the present analysis includes only the leading five sources of merchandise imports for each country. Remaining sources of merchandise imports are aggregated into a category titled ‘Other’. For the PLDs included in this study, the ‘Other’ category averages 21 per cent of total merchandise imports (see Table 4.1).

[11] Sourced from World Bank (2017). The full table is included under Annex 1.

[12] Information on composition of merchandise exports sourced from WTO (2018).

[13] Fuels and mining products comprise 75% of all Saudi Arabian merchandise exports (WTO 2018). Note that Saudi Arabia is not fully profiled in Section 5 because no meaningful information is included in the WITS database (World Bank 2017) concerning the destination of Saudi Arabia merchandise exports. Specifically, the ‘Unspecified’ category of merchandise exports for Saudi Arabia is reported to be 79.08 per cent.

[14] China is followed by the United States at US$1.55 trillion, based on 2017 data (WTO 2018).

[15] Other trade relationships also emphasise the importance of this theme. A timely example concerns the 2018 withdrawal of China from the management of overseas waste, a development which highlighted the extent to which some PLDs have hitherto been dependent on an authoritarian state for the recycling of domestic rubbish. See, for example, Semuels (2019) and Cansdale (2019).

[16] www.rainforest-alliance.org/

[17] www.msc.org

[18] According to the BBC (2019), Brunei announced the intention, on 3 April 2019, to apply the death penalty to offences “such as rape, adultery, sodomy, robbery and insult or defamation of the Prophet Muhammad”. However, following a celebrity-led boycott, Brunei’s ruler Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah was reported to have “extended a moratorium on the death penalty to cover the new legislation”.

[19] The Codepink Saudi Arabia campaign claims “It’s time to sever ties with the Saudi regime while it wages a devastating war on Yemen, murders its own people, tramples on human/women’s rights, and bullies all those who dissent with its policies”. See: https://www.codepink.org/saudiarabia

[20] Such a precedent was the Clapham Common movement which influenced Britain, in the early decades of the 19th century, to transition from the ‘still profitable’ practice of slavery. See Ferguson (2004:114-119).

References

AHRC (Asian Human Rights Commission). 2019. ‘Thailand: Election Did Not Meet the International Standards’. AHRC article dated 27 March 2019, sighted 16 April 2019 at http://www.humanrights.asia/news/forwarded-news/AHRC-FAT-001-2019/

ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations). 2018. ‘Thailand’s Automotive Industry: Opportunities and Incentives’. ASEAN Briefing date 10 may 2018, sighted 16 April 2019 at https://www.aseanbriefing.com/news/2018/05/10/thailands-automotive-industry-opportunities-incentives.html

British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). 2019. ‘Brunei Says it Won’t Enforce Death Penalty for Gay Sex’. BBC news article dated 6 May 2019 sighted 16 May 2019 at https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-48171165

- 2018. “China’s Xi Allowed to Remain ‘President for Life’ as Term Limits Removed”. BBC news articles dated 11 march 2018 sighted 15 April 2019 at https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-43361276

Cansdale, Dominic. 2019. ‘What’s Changed One Year Since the Start of Our Recycling Crisis?’. Australian Broadcasting Commission (online), 11 January 2019. Sighted 14 May 2019 at https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-01-11/australias-recycling-crisis-one-year-on-whats-changed/10701418

Davidson, Helen and Christopher Knaus. 2019. ‘Australian Weapons Shipped to Saudi and UAE as War Rages in Yemen’. Guardian (online) article dated 25 July 2019 sighted 25 July 2019 at https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2019/jul/25/australian-weapons-shipped-to-saudi-and-uae-as-war-rages-in-yemen

Ferguson, Niall. 2004. Empire: How Britain Made the Modern World. Penguin: Maryborough (Aust.).

Freedom House. 2019. ‘Freedom in the World 2019: Democracy in Retreat’. Downloaded 5 April 2019 from https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/Feb2019_FH_FITW_2019_Report_ForWeb-compressed.pdf (including “Freedom in the World Countries” table available at https://freedomhouse.org/report/countries-world-freedom-2019).

- 2015. ‘Democracy is Good Business’. Freedom House articles sighted 15 April 2019 at https://freedomhouse.org/blog/democracy-good-business

OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development). 2019. ‘Member and Partners…Current Membership’. OECD current membership list sighted 5 April 2019 at http://www.oecd.org/about/membersandpartners/

- 2017. ‘Report of the Chair of the Working Group on the Future Size and membership of the Organisation to Council: Framework for the Consideration of Prospective members’. OECD document sighted 17 April 2019 at http://www.oecd.org/mcm/documents/C-MIN-2017-13-EN.pdf

UNPD (United Nations Population Division). 2017. Spreadsheet titled ‘WPP2017_POP_F01_1_TOTAL_POPULATION_BOTH_SEXES’ sourced from the UNPD World Population Prospects 2017 website. Downloaded 13 May 2019 from https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/Standard/Population/

Semuels, Alana. 2019. ‘Is This the End of Recycling?’, in The Atlantic, 5 March 2019. Sighted 14 May 2019 at https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2019/03/china-has-stopped-accepting-our-trash/584131/

World Bank. 2019. ‘Doing Business: Training for Reform’. 16th Edition. Downloaded 15 April 2019 from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/975621541012231575/Doing-Business-2019-Training-for-Reform

- 2017. ‘World Integrated Trade Solution’ (WIT) database. Online trade database developed by the World Bank with partners including the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, the International Trade Centre, the United Nations Statistical Division and the WTO. Accessed 24-28 June 2019 at www.wits.worldbank.org

WTO (World Trade Organisation). 2018. ‘Trade Profiles 2018’. Downloaded 9 April 2019 from https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/publications_e/trade_profiles18_e.htm

[1] British Broadcasting Corporation (2018).

[2] According to an Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) report (ASEAN 2018), “Thailand is the 13th largest automotive parts exporter [shipping to over 100 nations] and the sixth largest commercial vehicle manufacturer in the world, and the largest in ASEAN”.

[3] An Asian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) interim report referred (AHRC 2019) to “fundamental democratic shortcomings” with the 24 March 2019 general election in Thailand.

[4] See WTO (2018:80). The United States was in second place with merchandise exports valued at US$1.55 trillion (WTO 2018:382).

[5] In its ‘Framework for the Consideration of Prospective members’, OECD restate (2017:4) the position that ‘OECD Members form a community of nations committed to the values of democracy based on rule of law and human rights, and adherence to open and transparent market-economy principles’.

[6] See OECD (2019).

[7] Based on review of merchandise import and other data included in ‘Trade Profiles 2018’ (WTO 2018) for the economies of Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxemburg, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, and United States.

[8] Note that imports into ‘prosperous liberal democracies’ from ‘Partly-free’ states are not included in the analysis.

[9] See UNDP 2017.

[10] The total is potentially significantly greater, as the WTO data (WTO 2018) used in the present analysis includes only the leading five sources of merchandise imports for each country. Remaining sources of merchandise imports are aggregated into a category titled ‘Other’. For the PLDs included in this study, the ‘Other’ category averages 21 per cent of total merchandise imports (see Table 4.1).

[11] Sourced from World Bank (2017). The full table is included under Annex 1.

[12] Information on composition of merchandise exports sourced from WTO (2018).

[13] Fuels and mining products comprise 75% of all Saudi Arabian merchandise exports (WTO 2018). Note that Saudi Arabia is not fully profiled in Section 5 because no meaningful information is included in the WITS database (World Bank 2017) concerning the destination of Saudi Arabia merchandise exports. Specifically, the ‘Unspecified’ category of merchandise exports for Saudi Arabia is reported to be 79.08 per cent.

[14] China is followed by the United States at US$1.55 trillion, based on 2017 data (WTO 2018).

[15] Other trade relationships also emphasise the importance of this theme. A timely example concerns the 2018 withdrawal of China from the management of overseas waste, a development which highlighted the extent to which some PLDs have hitherto been dependent on an authoritarian state for the recycling of domestic rubbish. See, for example, Semuels (2019) and Cansdale (2019).

[16] www.rainforest-alliance.org/

[17] www.msc.org

[18] According to the BBC (2019), Brunei announced the intention, on 3 April 2019, to apply the death penalty to offences “such as rape, adultery, sodomy, robbery and insult or defamation of the Prophet Muhammad”. However, following a celebrity-led boycott, Brunei’s ruler Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah was reported to have “extended a moratorium on the death penalty to cover the new legislation”.

[19] The Codepink Saudi Arabia campaign claims “It’s time to sever ties with the Saudi regime while it wages a devastating war on Yemen, murders its own people, tramples on human/women’s rights, and bullies all those who dissent with its policies”. See: https://www.codepink.org/saudiarabia

[20] Such a precedent was the Clapham Common movement which influenced Britain, in the early decades of the 19th century, to transition from the ‘still profitable’ practice of slavery. See Ferguson (2004:114-119).

References

AHRC (Asian Human Rights Commission). 2019. ‘Thailand: Election Did Not Meet the International Standards’. AHRC article dated 27 March 2019, sighted 16 April 2019 at http://www.humanrights.asia/news/forwarded-news/AHRC-FAT-001-2019/

ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations). 2018. ‘Thailand’s Automotive Industry: Opportunities and Incentives’. ASEAN Briefing date 10 may 2018, sighted 16 April 2019 at https://www.aseanbriefing.com/news/2018/05/10/thailands-automotive-industry-opportunities-incentives.html

British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). 2019. ‘Brunei Says it Won’t Enforce Death Penalty for Gay Sex’. BBC news article dated 6 May 2019 sighted 16 May 2019 at https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-48171165

- 2018. “China’s Xi Allowed to Remain ‘President for Life’ as Term Limits Removed”. BBC news articles dated 11 march 2018 sighted 15 April 2019 at https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-43361276

Cansdale, Dominic. 2019. ‘What’s Changed One Year Since the Start of Our Recycling Crisis?’. Australian Broadcasting Commission (online), 11 January 2019. Sighted 14 May 2019 at https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-01-11/australias-recycling-crisis-one-year-on-whats-changed/10701418

Davidson, Helen and Christopher Knaus. 2019. ‘Australian Weapons Shipped to Saudi and UAE as War Rages in Yemen’. Guardian (online) article dated 25 July 2019 sighted 25 July 2019 at https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2019/jul/25/australian-weapons-shipped-to-saudi-and-uae-as-war-rages-in-yemen

Ferguson, Niall. 2004. Empire: How Britain Made the Modern World. Penguin: Maryborough (Aust.).

Freedom House. 2019. ‘Freedom in the World 2019: Democracy in Retreat’. Downloaded 5 April 2019 from https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/Feb2019_FH_FITW_2019_Report_ForWeb-compressed.pdf (including “Freedom in the World Countries” table available at https://freedomhouse.org/report/countries-world-freedom-2019).

- 2015. ‘Democracy is Good Business’. Freedom House articles sighted 15 April 2019 at https://freedomhouse.org/blog/democracy-good-business

OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development). 2019. ‘Member and Partners…Current Membership’. OECD current membership list sighted 5 April 2019 at http://www.oecd.org/about/membersandpartners/

- 2017. ‘Report of the Chair of the Working Group on the Future Size and membership of the Organisation to Council: Framework for the Consideration of Prospective members’. OECD document sighted 17 April 2019 at http://www.oecd.org/mcm/documents/C-MIN-2017-13-EN.pdf

UNPD (United Nations Population Division). 2017. Spreadsheet titled ‘WPP2017_POP_F01_1_TOTAL_POPULATION_BOTH_SEXES’ sourced from the UNPD World Population Prospects 2017 website. Downloaded 13 May 2019 from https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/Standard/Population/

Semuels, Alana. 2019. ‘Is This the End of Recycling?’, in The Atlantic, 5 March 2019. Sighted 14 May 2019 at https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2019/03/china-has-stopped-accepting-our-trash/584131/

World Bank. 2019. ‘Doing Business: Training for Reform’. 16th Edition. Downloaded 15 April 2019 from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/975621541012231575/Doing-Business-2019-Training-for-Reform

- 2017. ‘World Integrated Trade Solution’ (WIT) database. Online trade database developed by the World Bank with partners including the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, the International Trade Centre, the United Nations Statistical Division and the WTO. Accessed 24-28 June 2019 at www.wits.worldbank.org

WTO (World Trade Organisation). 2018. ‘Trade Profiles 2018’. Downloaded 9 April 2019 from https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/publications_e/trade_profiles18_e.htm