In Indonesia, the issue of gender in policing continues to attract the spotlight. In a recent development, the Indonesian National Police (INP) stands accused of discriminatory treatment against female applicants by Human Rights Watch (HRW), which claims in its November 2014 report that the INP continues to require that female recruits undergo virginity tests.

Virginity Testing Still Required by the INP

Although recently denied by some, including Dra. Dewi Hartati, the Vice Head of the Ciputat Sekolah Polisi Wanita or Sepolwan (School for Policewomen) in South Jakarta (interviewed by the writer in July 2014), HRW assert that virginity testing has been in place since 1965, in disregard of all criticism and with no meaningful review. All female applicants are required to undergo obstetrics and gynecology tests, which includes a hymen examination as part of the physical test under Regulation No. 5 on Health Inspection Guidelines for Police Candidates. The implementation of Regulation No. 5 leaves female applicants with no option but to undergo the process, even if it’s humiliating to them. The relevant recruitment regulation is renewed every year through Chief of INP’s Decree, but its requirement and pre-requisites remain the same. According to HRW, the regulation is based on moral concerns - the bizarre logic apparently designed to prevent the recruitment of sex workers to the force.

Gender Gaps in INP

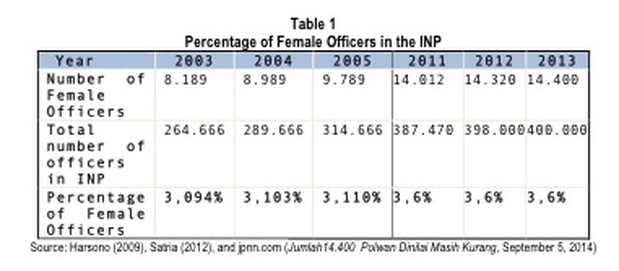

As well as issues of rights violation and gender-based discrimination, there is a striking gender gap in the staffing of the INP. Critically, the available data indicates that the number of female officers has not exceeded 4% over the last decade. Notwithstanding an increasing need for female officers to address complaint handling services, especially for cases related to women and children, the Unit Pelayanan Perempuan dan Anak (Women and Children’s Service Unit or UPPA) is still only available at the district police (Polres) level with very few female officers available for service. Whereas many cases of violence against women and children were reported to Polsek (subdistrict-level police), it can be roughly said that more than 90% of Polsek throughout Indonesia are lacking female officers. There has been criticism over this condition and calls for the INP to increase their number of female officers. Yet until now, the INP have not been able to meet the demand of a 30% quota (see Table 1).

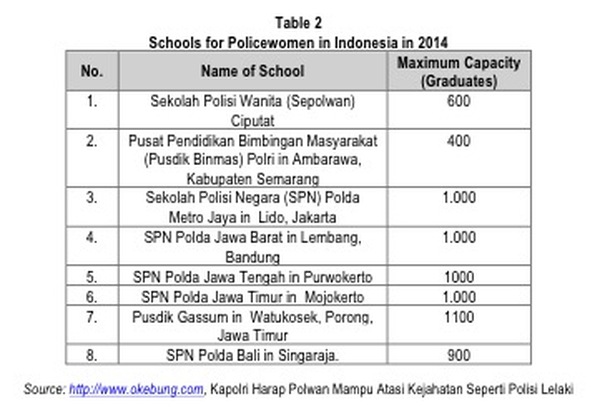

In an encouraging development, the INP Headquarters has recently changed their policy to increase the proportion of female officers from 3% to 10%, and recruited as many as 7,000 personnel from seven additional schools for policewomen, so in total there are eight schools for policewomen with an average of 890 graduates per batch per school.

Just recently, a female police officer candidate was expelled from the school for mid-rank officers because of being pregnant. She was one of 100 policewomen among a total of 800 (male candidates number 700) that enrolled in the training for mid-rank officers in November 2014 (Okezone.com, Hamil, Bripka Siti Tak Lulus Sekolah Inspektur, Wednesday, November 19, 2014). Furthermore, the regulations not only prevent pregnant and breastfeeding women from accessing education opportunities within the INP, but also from accessing education or capacity building opportunities delivered by external organisations, including the Jakarta Centre for Law Enforcement Cooperation (JCLEC). These various practices highlight the prevalence of double standards, as male police officers are not treated the same way or expected to conform to the same norms and limitations. From the examples profiled above, it is apparent that the INP practices gender-based discrimination and the violation of women’s rights in their daily practice, and it would appear that gender equality issues are not yet taken seriously among the internal ranks of the INP.

Age Discrimination

In addition, female officers wishing to enroll in higher education and vocational training also suffer from age limitations. For example, 21 is the maximum age for Brigadier-level training and for entry to Police Academy and for mid-rank officer course the maximum age is 28 (with Bachelor’s degree) and 30 (with post-graduate degree). It is common for female officers to miss the opportunity for further training and career advancement, especially for married female offiers because of their domestic responsibilities. Once they no longer have young childen, female officers have usually passed the maximum age required and are no longer eligible to participate in training. The obstacles preventing female officers from accessing mid-level training complicate access to advanced training opportunities. For example, the external courses conducted by JCLEC are only open to the limited number of female officers who hold higher rank (interview with JCLEC, July 2014).

Proportion of Women in Senior Positions

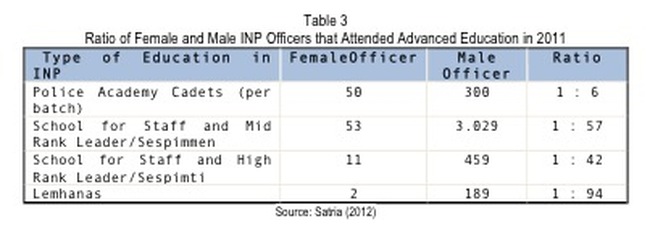

Given the range of obstacles restricting female officers from accessing education and self-development opportunities, it is quite remarkable that female officers (who occupy less than 4% of INP positions overall) still manage to access advanced training in the numbers shown in Table 3 below.

Female Officers Assigned Peripheral Duties

Gender segregation is also present in the assignment of officers to particular police functions, with the number of female officers assigned to administrative tasks much higher than other tasks. It is estimated that approximately 70% of female officers are allocated to administrative tasks and coaching (Harsono, 2009). Despite the lack of programs to prepare policewomen for operational tasks in the field, stereotypes and gender beliefs continue to influence the gender segregation of work in the INP. Recent research (interview with the Bureau of Human Resources Police Headquarters, July 2014) reveals a work culture in which women are considered physically weaker, more emotional, dependent and submissive such as to impede them from conducting serious police duties professionally, in particular those tasks related to intelligence and criminal investigation. Unfortunately, this suggest that little has changed since the publication of an Institute for Defense Security and Peace Studies (IDSPS) report in 2008 (IDSPS 2008) which identified the following basic assumptions underliying the assignment of women to particular duties:

- Female officers are considered more thorough at performing administrative tasks.

- Female officers should not be burdened with heavy duties or a night shift due to natural, ethical and normative reasons.

- Female officers have questionable ability to perform operational duties, especially in the field of criminal investigation and intelligence as well as other heavy duties.

- Female officers have many limitations that lead to less effective results (than their male colleagues) and require escort in order to perform better in the field.

- Female officers may deliver a reduced level of professional performance, especially when they are married and/or get pregnant.

Challenges for Gender Mainstreaming in INP

In recognition of the need for gender mainstreaming, a Telegram proposed by the Chief of INP (No. Pol. : ST / 839 / VIII / 2003 on socialisation of gender mainstreaming and the Child Protection Act) was adopted on August 13, 2003. In 2008, after half a decade of implementation, the Institute for Defense, Security and Peace Studies (IDSPS) identified (IDSPS 2008) a number of initiatives that had been launched in response to this regulation, including socialisation of gender mainstreaming within Headquarters (HQ) and Polda (2003) and socialization of the Child Protection and Anti Domestic Violence Acts within HQ and Polda (2003 – 2004). In a key initiative, a Ruang Pelayanan Khusus (Special Service Unit or RPK) was formed in 2004 to tackle gender-based violence (2004) however, as a non-structural unit unable to offer promising career opportunities and with no budget allocation, few female officers were initially interested in joining this unit. Fortunately, under Regulation of Chief of INP No. 10 Year 2007 the RPK was transformed into the UPPA (referred to above). Now operating as a structural unit with its own budget, the UPPA is headed by a female officer with minimum rank equivalent to Senior Inspector. It is understood that UPPA personnel have continued to receive capacity building on issues of gender equality, gender based violence, child abuse, and human trafficking.

While the establishment of the UPPA is an example of a step in the right direction, the IDSPS found in its 2008 analysis (IDSPS 2008), that the weak conceptual awareness on gender equality and lack of commitment and political will of INP to seriously adopt gender mainstreaming into practice remained an underlying cause for the absence of a systematic approach. It is now over a decade since the circulation of Chief of INP’s Telegram in 2003, and the various topics examined in this article demonstrate that gender mainstreaming within the INP continues to be an uphill battle.

* * *

For the INP to be brought into the 21st century and gender mainstreaming to become a reality, sporadic activities and stand alone-projects will never be enough. Serious engagement with gender mainstreaming means INP should take real steps to systematically close the gender gap. Collecting statistics (disaggregated data by sex) and qualitative information on issues affecting female and male officers as well as gender analysis identifying existing inequalities between male and female officer is the first step to overcoming the gap. A second step is for INP to consistently boost the number and quality of female officer at all levels and across all departments / policing functions, and enable a more gender sensitive working environment by providing equal opportunity for the personal and professional development of all personnel. All these efforts can only give the maximum, wider and traceable impacts if INP develops a gender mainstreaming policy and framework and adopts it into their strategic planning.

SSD Associate Eka Rahmawati is based in Surabaya, Indonesia. She served as National Consultant on a 2014 Evaluation of the Jakarta Centre for Law Enforcement Cooperation (JCLEC).

Harsono, Irawati. Pengarusutamaan Gender dalam Tugas-Tugas Kepolisian, Panduan Pelatihan Tata Kelola Sektor Keamanan untuk Organisasi Masyarakat Sipil: Sebuah Toolkit. ISDPS. Jakarta. 2009

IDSPS (Institute for Defense, Security and Peace Studies) . Seri 7 Penjelasan Singkat (Backgrounder): Gender Mainstreaming di Kepolisian. IDSPS. Jakarta. Juni, 2008

Satria, Riri. Kita Kekurangan Polisi Wanita, Sebuah Catatan Menyambut HUT Polwan ke 64. http://ririsatria40.wordpress.com/2012/09/19/kita-kekurangan-polisi-wanita/ accessed 25 December 2014

Web:

Human Rights Watch http://www.hrw.org/news/2014/11/17/indonesia-virginity-tests-female-police

Profil Unit Pelayanan Perempuan dan Anak, http://uppabareskrim.com/sippa/links_menu.php?op=profil accessed 30 December 2014

Perwira Tinggi Polwan dari SEPA, http://sipsspolri.com/perwira-tinggi-polwan-dari-sepa/ accessed 30 Desember 2014 Syarat Pendidikan Polri, http://humas.polri.go.id/informasi-publik/Documents/Syarat%20Serdik%20Dikbangspes-2014-1.pdf accessed 28 December 2014

News:

DPR Kritik Minimnya Jumlah Polwan, http://www.tempo.co/read/news/2013/03/21/173468408/DPR-Kritik-Minimnya-Jumlah-Polwan accessed 30 December 2014 Hamil, Bripka Siti Tak Lulus Sekolah Inspektur, http://news.okezone.com/read/2014/11/19/337/1067940/hamil-bripka-siti-tak-lulus-sekolah-inspektur accessed 30 December 2014

Jumlah14.400 Polwan Dinilai Masih Kurang, http://www.jpnn.com/read/2014/09/05/255899/Jumlah-14.400-Polwan-Dinilai-Masih-Kurang- accessed 25 December 2014

Polri siapkan delapan lembaga pendidikan untuk 7.000 Polwan, http://www.antaranews.com/berita/426588/polri-siapkan-delapan-lembaga-pendidikan-untuk-7000-polwan accessed 30 December 2014

Seribu Polwan Dilantik di SPN Purwokerto, http://www.pikiran-rakyat.com/node/310196 accessed 30 December 2014